Al Dente

Each summer here in Texas that as the heat climbs, the rains stop and the temperature builds at a truly ferocious pace, I increasingly find myself standing trancelike on my front porch. My mind travels northwestward, through the pecan groves and the oak stands, the mesquite thickets, skimming over the Brazos, Pease, and Red rivers, further and further, leaving the cotton fields of the panhandle behind and finally soaring over the wild, high Texas plains and the deserts of New Mexico. This goes on for days, and for days I shake that vision off and I shake it off until something clicks—or snaps—and I recognize what I knew all along; there’s a long drive in front of me.

As with many of my lifelong habits, this started innocently enough. One August day a few years ago I got a phone call from my friend Evan Voyles, who is one of the strangest and most wonderfully interesting people I have ever met. We first met in Abilene, TX. I lived alone in a small stone house on College Street; Evan had a small house too, but shared his with four hundred pairs of custom made cowboy boots he'd collected from all over the Southwest. In addition to his boot collection, Evan also trade in Navajo blankets, antique firearms, knick-knacks and old neon signs, the kind you see advertising hotels, department stores, long defunct products such as Bull Durham Tobacco, Four Roses Whisky, AM radio stations, greasy spoon diners, in short any of the old, quirky stuff that that was

made when things were built not only to serve their purpose, but to be pleasing as well and built to last. Boot jacks that looked like bugs whose antennae gripped the heel of one’s cowboy boots to help pull them off, not to mention another, more prurient style that was no doubt marketed to the lonesome cowboy.

And the thought of just taking off and heading up there, escaping the heat and the progressing desolation of Abilene swayed me and so go I did, unintentionally setting a course that I’ve followed—in various ways—ever since.

*****

A few years later I found myself living in Denton, Texas pursuing an advanced degree in a field that most people think very little of and it was August again and again it was dreadfully hot. I was living in an old, two story farmhouse and the four window unit air conditioners had little noticeable effect other than running my electric bill into the triple digits. At night, of course, the temperature would taper off a bit and I spent a great deal of time on the front porch drinking cold beer and waiting for the house to cool down while Tejas, my dog, sensibly lay dreaming in the yard.

The morning after one such evening as I reflected on my responsibilities around home, books I needed to read, the waist high Johnson grass in the back yard that needed to be burned or baled and various things of that ilk, I began to feel a creeping dissatisfaction and trying to dodge it, I got into my junk pile of a truck to run into town. I slammed the door shut, trying to sit without sitting on the baking vinyl seat as the heat inside the vehicle enveloped me like a malevolent presence; when I took my sunglasses off the dash and put them on, the metal ear pieces seared my temples. I looked around the cab as if for the first time, noticing the cracked dashboard, the little square of discolored glass on the windshield where the rearview mirror used to be, the steering wheel worn smooth in places—not ten and two o’clock, but fittingly enough, high noon—from the countless other lost errands that had filled years long vanished. After a couple of minutes of driving, I began to sweat, thousands of tiny streams coursing down my ribs, down my back, everywhere, and I had the irrational thought that all of my body fluids were going to leak out and I was going to die.

Sweat dripped stinging into my eyes and the asphalt, heated to seemingly black incandescence looked like nothing so much as a river of tar and hissed under the vehicle’s tires. I stopped at a red light and, looking across the intersection, I just gave up, made an illegal u-turn and followed the actual tracks I’d left in the sun softened road back home.

******

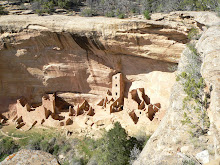

Later, after failing at all the little tasks one must undertake to keep a household even as tenuous as mine clunking along, I picked up an essay from The New Yorker my mom had mailed to me. It was about the Anasazi Indians, a subject which had never held much interest for me and that of late, had positively taken on the proportions of some slow and unearned punishment. I was working part time as a skilled laborer—adjunct faculty—at the local university and it seemed as if all my students the past semester had become infatuated with “New Ageism” a pseudo-philosophy in which the Anasazi loomed large. Each student seemed to believe they alone had made the discovery and essay after essay extolling the benefits of New Ageism as a virtual panacea for all of life’s little insults and inadequacies piled up on my desk. Even shackled by convoluted prose and grammatical errors that would have made an illiterate field hand blink, the gospel of the Anasazi sang from the pages. I knew the story. The Anasazi were peaceful, cliff dwelling race who—at the height of their cultural ascendance—mysteriously vanished, leaving only their Kivas, or Big Houses, and their belongings to remember them. This willful abandonment of their, as one student put it, “highly collectible textiles and pottery” was frequently offered as proof positive that not only were they above wallowing in the gruel of commerce, it followed that they been taken to live beyond the stars by space aliens who valued the Anasazi’s cavalier attitude towards their kingdom of dust.

I tossed the article away but as it spiraled towards my reading desk, the word “cannibal” caught my eye. Now, cannibals are—to my mind, at least—the ultimate humanists, and as such are always interesting. For instance, only the most tepid of vegetarians would dare deny that Queequeg is the one redeeming human character in Moby Dick. So I sat down and for the next twenty minutes found myself entranced. It seems that in the late sixties a certain a forensic pathologist named Christy Turner was researching a cache of human remains that had been “harvested”—his term—at various times over the past hundred years from Anasazi dwelling places in the Chaco Canyon region of New Mexico. Regarding the armature of mankind is always rewarding, but under his scrutiny the peculiar condition of the bones became increasingly freighted with a darker significance. Finally, to the astonishment of some and the fury of others, he concluded that the bones—though undeniably human—bore the tell-tale signs that even the gentlest of chefs must leave behind and were in effect “food debris.” He based all this on a variety of evidence such as cuts and nicks on the bones from having the meat flayed from them, scorching at the base of skulls from having been placed face-up in a bed of cooking coals, bones split for their marrow and one heinously unique characteristic—usually found on a femur—which he termed “pot polish,” which is a smooth-worn ring on the bone caused by its being used to stir the contents of their earthen cooking pots. He postulated that about the same time Charles III was bribing the Rollo the Viking with what would become Normandy, the Anasazi had their own problems. They were being infiltrated by a heavily armed band of Toltec thugs from Central America.

These interlopers brought with them, among other things, a type of decorative chipping of teeth, tropical parrots, macaws, and a complete—if chilling—cosmogony. But they also carried within them a hunger for human flesh mixed with corn meal, which they called—in either a burst of deeply disturbing humor or appalling candor—“Man Corn.” Far from being whisked away in the comfort of filtered oxygen and nuclear precision by friendly visitors from Out There, the Anasazi undertook another, arguably stranger exodus. In a stunning manifestation of the evils inherent in falling into cliché, the Anasazi, Dr. Turner concluded, ate themselves out of existence.

I put the article down and looked around in that mild, dumb confusion that extremes—cold, heat, pain—can engender. The image of severed heads, clouded eyes staring sightlessly from the coals and into the inviting cool of a high desert night crept into my mind like an unwelcome guest. Cook steam flowing from human flesh to float in a swarm of stars. It was hot and still in the house and I got up and moved around, picking up one book then another, straightening a photograph here, an ashtray there.

I took a cold shower in the vain hope that it would have some effect either on the heat or on my thoughts. I stepped dripping from the bathroom and without toweling myself dry, put on a pair of blue boxer shorts with green fish on them and walked out to the street to check the mail.

Several bills, an issue of Western Horseman magazine, a flyer from Wal-Mart, a postcard advertising oil changes and kidnapped children, a bounced check notice.

I went into the bedroom and packed immediately. Chaco Canyon by way of Santa Fe to check up on the lost Anasazi sounded just about right.

******

For over twenty years now, my favorite form of transportation has been the Toyota Landcruiser, model FJ-40. It’s like a jeep, though more rugged and infinitely less comfortable. But driving with the top and doors off is a great way to see some country and one really gets a sense of becoming part of the place you’re traveling through, similar in ways to going horseback. Afterall,the journey is the point, not the arrival.

I went out to the car shed and raised the hood of the vehicle, checked the oil and looked for any obvious signs of impending failure: cracked hoses, frayed belts, corroded battery cables. A dead mouse lay curled on the intake manifold next to a drop of pthalo green anti-freeze, which I understand for them is as irresistible as it is fatal. I retrieved an eight millimeter socket from a canvas lineman’s bag under the driver’s seat and torqued the hose clamp down, forcing another drop of poison from between the hose and the manifold. I didn’t think they’d eat it, but I tossed the mouse into a steel trashcan so my cats wouldn’t be tempted, and leaving the hood open, started the vehicle and pulled around to the front of the house.

While the engine cold idled roughly, I threw my duffel bag into the back of the FJ-40, put my pistol in its lockbox and stowed an old C.C. Filson wool jacket in a rucksack strapped behind the passenger seat, remembering again how I had longed for it once when climbing the grade into Raton Pass, I’d left the warm desert floor and found myself in a blowing snowstorm. I went and checked the motor once more, noticed that the leak seemed to be fixed and shut the hood.

By the time I finished my preparations the day was much advanced, but that was fine with me. As with many things, when it’s time to face the road, the night is best.

I climbed behind the wheel and sat in silence, checking points off my mental punch list. I had had only the vaguest of itineraries, one that essentially followed the path of least resistance. Priority One was to simply put a sufficient number of miles between myself and the blast-furnace heat of a Texas August. Barring a breakdown or some other calamity, I’d been in Santa Fe in a day. That would give me time to rest up a bit, go to Indian Market and look around, tire of that and then spend a night bouncing in and out the various bars, restaurants and what have you until I ran out of cash or desire, though of course it’d be the money. Early the next morning I’d cruise the roughly 150 miles northwest to Chaco Canyon, find a place out on the desert to camp and look around. Maybe I’d see a ghost or maybe I’d see a spaceship canting down to spirit me away. Quein sabe? I did know el coyote would be crying in the wilderness and that was enough justification in its own right. It wasn’t too much of a plan and I thought it had a nice, graceful curve to it. Minimalist. I may not have known exactly where I was going or when I’d get there, but I figured either way I’d be way ahead of schedule.

It was almost sundown when I wheeled out of the driveway, and the sun, filtered through the late afternoon haze, looked like a flat disk of molten copper.

******

Within three hours I was on Highway 287, angling northwest towards the Panhandle and marveling again how increasingly barren and rough the westward country is. The towns along the highway are sparsely populated as most everyone who is born out there does their best to grow up somewhere else. And though I'm sure boredom is a constant, it's a good place to see falling stars.

It was getting on to midnight when I caught the first meteor at the outside of my peripheral vision just as it faded away. I drove on awhile, the heat still oppressive even though it had been full dark for three hours. Suddenly, an “earth grazer” shot straight across the sky, east to west like an incandescent freight train barreling through the firmament.

Now, I’ve spent the better part of forty years outside, and odd as it is, I’d somehow managed to miss noticing the annual Perseid meteor shower. But I was noticing it now and, in the parlance of the King James Bible, I was “sore amazed.” For the next thirty or forty-five minutes I drove through the dark country-side and craned my neck around watching the meteor shower and trying—sort of as an afterthought—to stay on the road. I ran off the shoulder a couple of times, and almost got ticketed while racing through Clarendon whose street lights, though futile and frail, still cast enough illumination to hide the sky.

When I saw Amarillo glittering on the horizon I pulled off the road, lay across the hood of the vehicle and watched the sky for another hour or two.

And then it all stopped, as abruptly as it had begun.

******

I crossed the New Mexico line about an hour before dawn. Driving through the much celebrated gloaming is—for a variety of reasons—dangerous in any case, but when you’re as wind-blown and road weary as I was it’s just plain stupid, so I pulled off at the first open place I saw, one of those mega-truckstops that sells everything from baby formula to hard core pornographic videos.

There was a weathered woman of indeterminate age sitting at the cash register with a look of absolute and timeless disinterest that rivaled the Easter Island crowd and an emaciated waitress could have passed for a hard thirty or a girlish eighty. She just materialized at my table and she’d obviously been crying and her eyes, puffy and bloodshot, offered no window at all as she wordlessly took my order. She vanished into the kitchen and I never saw her again.

Not long afterwards, the cook or somebody else in a grime spattered apron brought it to my table and cheerfully asked if I’d like anything else. He stood on one foot and then the other and when I said “no” he shrugged his shoulders, smiled and spun around as if on parade, departing like a stained shadow.

I'd wanted to hit Santa Fe around seven or eight so I could go to this little hole in the wall on Guadelupe that serves huevos rancheros mixed with fried potatoes, jalapenos, corn, black beans, sausage, onions and a bunch of garlic. It comes sizzling in a heated skillet and they don't have to tell you “Don't touch it, it's hot.” Instead, I sat staring down on a styrofoam plate at a deep fried and tangled mass of something that might or might not have been alive at some point in the not too recent past and drenched in a lake of coagulating grease that looked to be one shade past radioactive. It had been advertised as “Buffalo Wings”—a name of seemingly endless confusion for me—and after reading Dr. Turner’s work, the words “perimortem mutilation” and “food debris” sprang uncomfortably to mind.

I looked around the near deserted restaurant. In one booth a haggard looking couple peered forlornly through the dirt-streaked plate glass window at a landscape that in the monochromatic light of early morning looked nothing short of alien. A boy of 12 or so—obviously theirs—crouched in another booth, happily squirting honey from a bear shaped dispenser into his mouth and licking the top and sides of the container in a delirium of pure animal ecstasy. I looked back at the other table to where his father occasionally glanced at him, though his mother still seemed transfixed by whatever visions the parking lot held for her.

I threw a ten dollar bill on my table and headed for the door.

As I swung up into the Landcruiser I noticed a rusted out Chevy pick-up with Florida plates and an overloaded U-Haul trailer with what looked to be the entirety of some family’s earthly possessions. In contrast to the battered truck, the trailer looked to be brand new and had a festive decal depicting a Killer Whale in a splash of ocean with “South Dakota” of all things lettered underneath it.

******

Ten a.m. caught me somewhere out in the desert, tired, hungry and trying to recapture the time I'd lost stargazing in Texas. For the first hour or so after you cross the border, nothing about the country much changes. Eventually though, the elevation begins to mount, traffic becomes more sporadic and you are truly left to your own devices. Which in my case that morning was that I kept thinking about the Anasazi and the meteor shower of the night before—two things that I don’t know much about—and thinking that they were metaphorically linked. It seemed to me that both had been brief and brilliant, leaving in their passing a transitory beauty, a gift. At any rate, one thing to be said in favor of ignorance is that you find cause for wonder in the damnedest places.

I kept going and the air became cooler and I began to see scattered bunches of pronghorn, a few blue quail and once, a rattlesnake sunning itself on the blacktop. There had been a heavy dew the night before and the greasewood and octilla cactus were limned with moisture.

A note here about driving in New Mexico—and this can be either a blessing or a curse—there are almost no highway signs. In Texas and some other states there will be signs that say "El Paso 445" or "Highway 377 2 Miles" and the like. “Slow Children Playing,”—however that might be construed—that sort of thing. When you are approaching an exit, it will be marked and a sign will inform you what to expect at the other end of that road as well.

As I said though, signs in New Mexico are as sparse as good intentions among the damned and really, just about as useful. When you do find one, perhaps after hours of wandering alone in bewilderment, it's apt to declare "Picnic Area 1 Mile," or something equally useless. Unless, of course, you’re struck with the sudden urge to eat a sandwich out on the malpais.

Only the largest highways, such as Route 66, which cuts east to west from North Carolina to California, are marked with "exit to" signs. Evidently even the New Mexico Department of Transportation couldn't ignore that one. All the rest are marked where they intersect. So if you're driving north and see an overpass, you have to exit and read the sign is facing east to figure out if it's a highway you'd care to be on.

But in spite of this I eventually made it to Cline's Corners, fueled up and headed west for the final leg of that part of my journey.

******

I pulled into Santa Fe about mid-afternoon. The smell of pinon smoke drifted like incense on the cool mountain air and the sky was as blue as a sharecropper’s soul. A bank clock said the temperature was sixty-eight degrees. After twelve hours on the road it felt and smelled like a paradise.

I drove down to the square, taking in the sights. Everywhere there were Anglo-Saxons striding around, carrying huge shopping bags emblazoned with the fanciful names of boutiques such as Silver and Sage, Sunset Canyon, Simply Santa Fe, that sort of thing. Most were dressed in nouveau west: 275.00 a pair blue jeans, shiny new cowboy boots and designer western hats. Also, of course, there were the local kids hanging out in the park in the middle of the square smoking dope and checking out the gringos, a few Indian women kneeling on hand woven blankets selling jewelry and here and there clusters, of sunflowers ten feet tall with stalks as thick as a big man’s wrist and heads that looked platters. It was pretty in its way and vibrant, certainly, but none of it jibed with the history of the place, which seemed to have been brushed aside and swept into the shadows of the mission San Miguel.

I stopped at a red light and nodded amiably to the passersby who rushed up and down the street. They looked like product junkies on a turbo-shopping binge. Most avoided making eye contact with me, and the ones who did quickly looked away. I couldn't blame them. With the top and doors off my Landcruiser it was easy for them to give me a good, long, once-over and what they saw wasn't too delectable. I had on a pair of worn out Wrangler jeans, my old M.L. Leddy boots and a blue chambray shirt I'd sweated through so many times salt ringed the collar and armpits like pond ripples locked in sudden stasis. Wearing that shirt was like hugging Lot's wife after her unfortunate backward glance.

Physically, though, I didn't feel too bad. My joints and back were a little stiff from the drive, but all I needed was a shower, a Jack Daniels and a steak, though I would have settled for two of the three.

When the signal changed I shifted out of neutral into first and eased off the clutch. Halfway through the intersection an improbably blond woman driving a forest green Range Rover ran the light and almost killed me. As she disappeared in a wash of new car smell and dust she instructed me to perform a carnal act upon myself that is both anatomically and physically impossible—though I’ve managed it de facto several times in my life—and followed up with a scream of invectives that would have made the Marquis de Sade blush and cross himself. Shaken, I drove on up Washington Avenue and checked myself into the old Santa Fe Penitentiary, though these days it’s called the Inn of the Anasazi. How could I not? I threw my duffle bag through the door of a room that now opened at the whim of its occupants and went straight down to the cantina.

******

The bar was filled past capacity with locals and vacationers of every stripe. One “local” who turned out to be a real estate investor from the San Fernando Valley, stood at the end of the bar raving drunkenly to no one in particular about a house he’d just sold for an obscene profit. To my right, a small, thin built man was trying to draw my attention to a concho belt he was wearing, claming he’d turned down 5000.00 dollars for it because it was worth ten and “I ain’t no swingin’ dick…” whatever that’s supposed to mean.

I stepped out onto the street and spent the rest of the evening walking around, into and out of bars and becoming increasingly dissatisfied.

******

I didn't realize it at the time but this proved to be the general tone of the rest of my night in Santa Fe. I was lectured in bars by surly drunks who could barely slump upright. A waitress at Steaksmith’s Restaurant refused to take my order after I asked, in a burst of ill-advised frivolity why "free roaming range chickens" were "more balanced" at the point of death than say, Bo Pilgrim's. It seemed to me that after dodging hawks, coyotes, eagles and snakes they’d be skinny and nervous as a crack junkie at a police convention, if not positively deranged. I front loaded the “de” part, hoping she’d get the pun, but it was no use. I was just beginning to explain to her that when my entrée came I would be looking for signs of scalping, bones exhibiting cut marks consistent with dismemberment, femurs cracked open for their marrow and pot polish. She fled to the kitchen. The manager came out and tried to put it all into perspective, but it was no use. I finally realized that I was the biggest part of the problem and in a gesture of bonne homme, ordered the Chicken Kiev but my new server told me they were “fresh out.” I paid for my drink and left.

******

The next morning I lay in bed longer than usual. The night before had left me a little flat and I decided to skip Indian Market entirely. Checking the weather station revealed a storm brewing in the San Juan’s and much rain was expected. Drawing back the curtains, I looked at the menacing sky and thought Maybe I better head back to Texas, back to my own country.

I dragged my cleanest dirty shirt from my pack, put it on and decided it was past time to leave. On the way out, the desk clerk smiled politely and said “Vaya con Dios, senor.” I smiled at him, but hadn’t realized I was that transparent.

******

Outside I encountered two teenagers, a boy and girl, both about sixteen, sitting in my Landcruiser. Evidently they’d been there long enough to discover that the radio was hardwired direct to the battery and they were holding hands and listening to a tape of Townes Van Zandt. They didn’t seem alarmed when I walked up and put my pack into the back of the vehicle. We all looked at each other for a long moment and then I told them I had to go and the jeep was going with me. The girl smiled at me as only those in love for the first time can and the boy sighed with the despondence that, once again, only the first timer’s believe.

I got in the Landcruiser, fired it up and pointed it northwest. At the edge of town I filled the tank and checked the oil. While waiting to enter the highway I suddenly caught the scent of the girl’s perfume and realized that I not only had a choice to make, either option was the right one. I could head south back to Texas and hope for more falling stars and that long string of night. Or, I could push on to Chaco canyon and search for those other fallen stars. Suddenly, my world seemed boundless.

28 August 2009

Al Dente

travel ranch university

Anasazi,

cannibals,

CC Filson,

FJ-40,

Landcruiser,

New Mexico,

Roadtrip

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment